To have a chance of averting the most extreme climate disaster the biodiversity crisis, and related food and refugee crises, the world must halt tropical deforestation and degradation and restore significant amounts of former forested areas. We are continuing to head in the wrong direction, but is there some light beginning to shine?

Through 2020 12 million ha of tropical forest was lost, 4.2 million of that from primary forests. Brazil lost 1 million ha of Amazonian forests in 2020, amounts not seen since 2010 and 3 times its target rate according to its own national policy. Deforestation in the tropics continued unabated despite calls from NGOs for a moratorium. In 2021, Brazil saw another spike in deforestation rates. Already burnt in 2020 with 30% of its area devastated, the Pantanal, the largest tropical freshwater wetland, burnt for the second year in a row with an estimated total of 0.68 million ha lost in 2021, putting this ecological wonder at even greater risk of collapse. The so called “savannisation” of the Amazon is predicted to lead to heat stress and significant health risks for over 11 million people in Brazil by the end of the century due to regional climate change caused by this fast pace ecological destruction. We use Brazil here as an example, but this trend is being seen in much of the humid tropics.

The increase in deforestation, especially Brazil, is due to national policy enforcement failure. Gains were made in the Amazon during earlier this century due to concerted efforts by industry and government. An example of this is the Amazon Soy Moratorium, an agreement by grain traders not to purchase soy grown on recently deforested land, which is estimated to have prevented 8,000 ± 9,000 km2 of deforestation over its first decade (2006–2016) of implementation, while soy output went up by 400%. These gains however were drowned out by the effect of the cattle industry which in 2020 had a disproportionate effect on deforestation rates in the Amazon. It is imperative that world governments, industry and consumers wake up to the disaster that looms ahead of us.

There was some good news in 2021. COP 26 saw world governments coming together and agreeing on several important climate change issues, although it is yet to be seen how these will be implemented by national governments. The Glasgow Climate Pact calls on governments to present increasingly ambitious climate actions. Coal is to be phased down and subsidies for fossil fuels to be phased out. The pact also calls for a doubling of climate adaptation funding for developing countries by developed countries. This is important. Investment in climate mitigation projects (such as reducing emissions by installing solar power generation) far outweigh adaptation projects which are inherently designed to safeguard the most vulnerable people against the effects of climate change such as droughts, floods and sea level rise. The latter is very much needed to avert climate tragedy amongst the world’s poorest people and an even greater refugee crisis.

In recognition of the enormous role that forests play in regulating our climate, 141 countries representing 90 per cent of the planet’s forests signed the pivotal COP26 Glasgow Leaders Declaration on Forests and Land Use, committing to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030. Importantly this declaration was signed by Brazil, Russia and China and, for those of us that are working hard to protect Panamanian forests, Panama.

At the conference President Biden of the US pledged to support the restoration of 200 million ha of forest by 2030, while President Duque of Colombia promised to protect 30% of his country’s territory by 2022. A sustainable trade commitment was made that represents 75% of key products that threaten tropical forests such as palm oil and cocoa.

Another interesting initiative is the High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People also known as 30×30 , which aims to conserve 30% of the planet (land and sea) by 2030. Currently only 15% of land and 7% of ocean is protected. However, this has come under some scrutiny since indigenous people, arguably, already conserve approximately 25% of the world’s land surface and their role must be acknowledged in this initiative and others.

Although world governments are largely on board with the COP26 climate pledges, their words are empty unless they can put these commitments into practice and to do that the private sector must be involved, especially in western democracies. Pledges by the world’s richest people do make a difference, if that funding can be used well. Recently, Jeff Bezos announced a further $2bn to add to the $1bn pledged earlier for his Earth Fund to help restore nature and transform food systems, as just one example of philanthropy. But this isn’t enough. It is estimated that it will cost $200bn per year up to 2030 to restore terrestrial nature (not oceans). To find this money the private sector must be involved. Industry must change the way it does business and governments must be held to account to push and pull the levers of the economy to provide incentives for this to happen. The soy, beef, palm oil, cocoa industries as well as precious metals and others must be able to make profit by doing the right thing and being a force for good (which is in their interest) while it must be costly if they aren’t. Government and industry have very clear roles in making sure that the planet remains a place that is inhabitable for everyone and ultimately it is up to us as consumers and voters to make sure this happens.

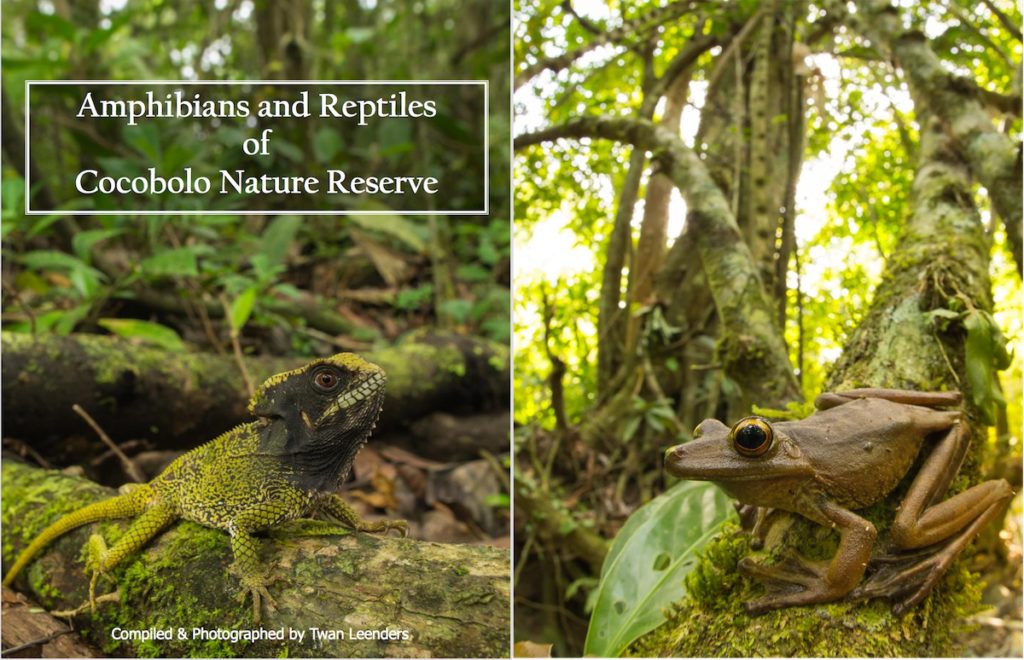

CREA is a small but essential cog in putting the meagre financial resources, committed to nature conservation, to good use. We are working hard to protect the Cocobolo Nature Reserve in Panama, to provide education and awareness of the role that tropical forests play in our lives, no matter where we live, and to provide resources to local communities so that they can preserve their environment and adapt to a rapidly changing world.

We hope that 2022 brings us good news for tropical forests and we hope that you might visit us in Panama at some point.